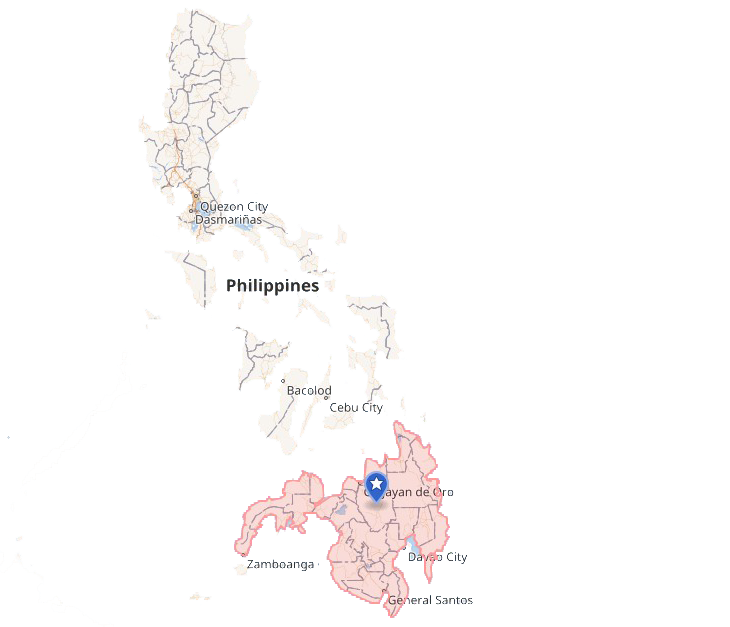

On May, 23 2017, Islamist militants from Abu Sayyaf and Maute groups took over the Philippine city of Marawi. Its liberation required more than 5 months of fighting.

The origins of conflict

Deep contradictions between the Muslim population of Mindanao Island and the central Philippine government started at the middle of 20th century. The Muslims demanded autonomy and every year they were more persistent radical.

The Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF) led by Nur Misuari has fought the government from 1972 to 1976. After they eventually settled for a peace deal the partisan struggle was continued by the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), created in 1981 by Hashim Salamat.

In the 1990s Mindanao has witnessed the ascent of Abu Sayyaf – the much more radical terrorist group composed of irreconcilable Islamists. The Philippine government had offered $5 mln reward for capture of its recent leader Isnilon Hapilon.

The Maute group was created by the Maute brothers in 2012. They became allies with Abu Sayyaf in the war for an independent Islamic state in the Philippines. On April, 2016 Hapilon was appointed as Emir of all Islamic State’s forces in the Philippines with his headquarters at Marawi.

Marawi is captured

In the mid-May 2017 Isnilon Hapilon arranged meeting with the leaders of Maute group to coordinate united actions against the government forces. On May, 23 the streets of Marawi became the battle arena between militants and police troops that were intended to arrest Hapilon and prevent the act of terrorism. The policemen were assisted by the Army, but the militants got reinforcements.

Islamists had captured Amai Pakpak hospital and raised the Black Banner of ISIS above the building. 500 Maute fighters attacked Camp Ranao military base that is home to the 103rd Infantry Brigade. Soon the militants had seized the city hall and two prisons, from which they recruited new members. All roads leading to Marawi were blocked. The city was overrun by terrorists.

First moves

The next day, on May, 24, fresh government reinforcements arrived to Marawi. They successfully recaptured hospital, city hall, and the University of Mindanao building. Fierce firefights on the city streets led to the mass migration of locals, although many of them had welcomed fellow Muslim militants at first.

President Duterte declared martial law in Mindanao and the Army promptly managed to besiege Marawi to prevent escalation of the conflict.

Philippine military created a special task force for Marawi in short time. It consisted of several thousands of soldiers including elite Scout Ranger Regiment, Light Reaction Regiment, and a Marine Brigade. They were supported by 150 armored vehicles and air force.

Furthermore Rodrigo Duterte reached an agreement with Maoist New People’s Army (NPA) and MILF that considered the government authority to be the lesser of two evils compared to bloodthirsty radical jihadists. Thereby militants’ forces and support were considerably limited. Moreover, both NPA and MILF took part in battles with terrorists. Officials were confident that the liberation of Marawi would be a matter of weeks but the counter terrorist operation lasted more than 5 months.

The amount of terrorists in Marawi was not estimated precisely. At first Philippine Army had reported about 400-500 militants in the city but then the number grew up to 700-800, and in the end it was 920 eliminated fighters.

“Terrorists managed to strengthen their defenses, establish machine gun nests, disperse snipers, and lay explosives and bombs. All this has caused the great destruction and the loss of many lives”, — said Lieutenant Colonel of Joint Operations Group Jo-Ar Herrera.

Protracted fighting

For a number of reasons the quick victory over terrorists didn’t happen despite the advantage in numbers. The attacking forces generally need to have fivefold superiority over the defenders to make the successful assault of well-fortified city in a stationary warfare.

Relying on data provided by the Philippine military one can suggest that there were at least 1,000 terrorists in Marawi. Considering that some of the locals could have joined the militants, this number can be increased to 1,500.

By approximate calculation, the Scout Ranger Regiment and the Light Reaction Regiment had 700 soldiers each, and the Marine Brigade probably had around 1,000 fighters in addition to the several regular infrantry units. I doubt that the total number of deployed forces in Marawi exceeded 5,000 men.

However the command center of the Philippine Army apparently didn’t assume possibility of such large-scale actions in the city and therefore wasn’t ready to organize the infallible liberation campaign. The efficiency of combat solutions was also undermined by the lack of reliable data on the enemy. At first there were lots of incoordination between ground forces, artillery, and air support. For example, one of their airstrikes has killed 13 marines in a friendly-fire incident.

The Philippine Special Forces and the Marines have rich combat experience in jungle operations but very limited in street fighting. So the militants were purposefully preparing for the urban warfare to minimize the role of governmental air force and combat vehicles. The situation was even more complicated because of the presence of highly trained foreign fighters from the Middle East.

Most of the Philippine military equipment was also notably obsolete. The air support was implemented only by the American OV-10 Bronco jets from the times of the Vietnam War. Artillery and tanks were not used at the first stage of the operation at all. The armored car LAV-150 had weak plating and was ineffective on the city streets. Soldiers reinforced its hull with any improvised means including wooden planks to protect it from anti-tank devices.

According to the evidence from the first lines, soldiers were in great need for the firepower of tanks and artillery. Nevertheless the government intended to get off cheap. Because of this the most important moment was lost and the militants managed to create strong lines of defense. Limited firepower was holding back the advancement of the Philippine Army.

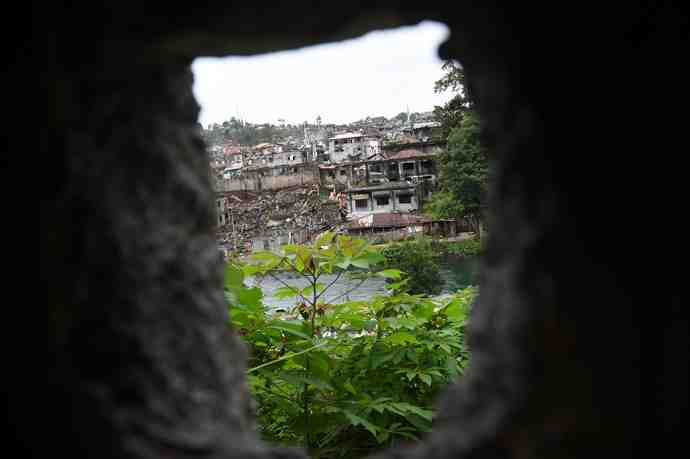

Marawi battle zone occupied half of the city with the population of 200 thousand, mostly Muslim. After 5 months of intense fighting the militants were expelled from half-destroyed buildings. The streets were filled with corpses, garbage, and rusty fragments of damaged vehicles.

Military assistance

Soon after the beginning of conflict the Philippine government has asked for help from foreign states. United States Special Operations Forces have arrived to the country but they weren’t taking part in fighting, being concentrated only on gathering intelligence information. Significant material and technical assistance was also provided by China. Near the end of the conflict President Duterte succeeded in signing the arms shipment deal with Russia.

In addition the Royal Australian Air Force agreed to make reconnaissance flights over Marawi. Operational officer of the Scout Ranger Regiment Captain Alex Estabaya said that skills learned from American Green Berets were invaluable during the fight.

The Philippine Scout Rangers are acknowledged experts in jungle warfare but they had completely different conditions during urban engagement. American Special Forces instructors on the other hand have the experience of battles on the streets of Iraqi cities, so they taught their Philippine colleagues melee combat tactics.

“They showed us how to clear rooms and the basic principles of close-quarters combat — things like entering with a small number of personnel and operating in small teams. The Green Berets also taught us how to exploit sensitive sites. We found documents in some of the buildings. We would cordon the areas and then exploit them and get all the available materials”, Captain Estabaya said.

He added that the Green Berets didn’t provide the Scout Rangers with counter-improvised explosive device training but they did teach other Philippine troops how to deal with booby traps and roadside bombs. It is worth noting that the Philippine soldiers encountered 1,500 IEDs in the city.

Colonel Romeo Brawer, deputy commander of the task force that eventually liberated Marawi told that Americans also trained the 700 men strong Light Reconnaissance Regiment, the only Philippine urban combat unit.

Militants used the bombs made from conventional ordnance and fireworks and placed them in backstreets, doorways and windows. They detonated explosives using pressure plates, wires, or mobile phones.

United States intelligence ensured the success of targeting the insurgents with 105mm and 155mm artillery and 500-pound aerial bombs dropped by the Philippine FA-50 jets. American and Australian P-3 Orion surveillance planes and drones flew over the city and notified the location of the enemy.

Moreover the Americans used night surveillance and thermo graphic cameras. As Captain Estabaya said, they saved lives of many soldiers by tracking heat signatures of terrorists inside the buildings.

Combat tactics

At the same time the Scout Rangers developed their own battle tactics.

“We call it the four Fs: fire, forward, fortify and fire again”, — Captain Estabaya recalled.

He indicated how the troops captured a riverside neighborhood by the suppressive fire on the enemy, advancing to a dilapidated building, taking cover behind the walls, and firing inside to detonate enemy’s IEDs.

The South East Asian insurgents applied the Iraqi combat tactics. They breached holes in the walls and fortified buildings with sandbags to move around freely. Also like the Iraqis they used small reconnaissance drones. Colonel Brawer admitted that the government forces shot down 7 drones during the campaign.

Raffy Tima, a Philippine journalist described these events in the GMA News article published on November, 4 2017. He had a chance to walk inside the enemy tunnels and concrete jungles of Marawi after 5 months of clashes with terrorists.

First Person

It was my third time inside the main battle area. But according to members of the Third Scout Ranger Battalion I was with, this would be the first time a journalist will see the tunnel system their enemies used in the cat and mouse game to retake the city of Marawi.

For journalists who covered the battle of Marawi, the main battle area was for the most part a mystery.

Stories of how the terrorist group used extensive tunnel systems and fortified sniper positions to hold on to Marawi for almost five months were never really independently verified.

Until Now

The Scout Rangers led me to a two-storey house where, for weeks, snipers halted their advance into the city. The elite soldiers said they could not even cross the street because of M203 grenade and sniper fires coming from this house.

One soldier tried. But he was struck in the shoulder, a sniper’s bullet exited through his face, shattering his jaw. Vastly superior in firepower, the Scout Rangers hit the house with all they have until the sniper’s gun fell silent.

But as soon as they entered the house, the volley of enemy gunfire returned. That’s when the lead scout saw the small hole on the farthest wall of the living room, spitting out flashes of hot lead, the bullets coming straight at him. Undeterred, he fired back forcing his adversary to stop.

More Scout Rangers poured into the room guns blazing towards that small hole on the wall. And then silence.

Hole in the Wall

Terrorists punched holes into concrete walls for the snipers. The soldiers cautiously advanced, expecting the sniper on the other side of the wall to be either dead or gravely wounded.

Terrorists punched holes into concrete walls for the snipers. The soldiers cautiously advanced, expecting the sniper on the other side of the wall to be either dead or gravely wounded.

But as they’ve been repeatedly told during close quarter battle training: the danger is not over until you open the door and see the body of the enemy. They had to clear one more room before they could finally reach the small door leading to the sniper’s nest, a storage room underneath the staircase.

Opening the small door wide enough for a hand grenade, a soldier tossed one inside. Seconds after it exploded, they barged in. But the sniper was gone.

It is likely that the sniper assigned here was a foreign fighter, according to the Scout Rangers. These so-called jihadists were assigned in strategic positions, their sniper’s nest usually close to an escape route allowing them to reposition without surfacing on the streets.

The foreign fighters, the soldiers said, were very valued by the terrorist group.

The tunnel

When I entered the sniper’s nest, the faint smell of gunpowder mixed with the distinct odor of damp soil hit my nose. Five feet from the snipers hole was the entrance to a tunnel dug on the concrete floor. The soil from the tunnel had been packed in sacks and used as protective sandbags.

The tunnel was shallow, only five-foot deep. At the bottom, it split into two passageways. The soldiers said one led to the house across the street and the other to an exit at the back of the house.

The tunnel was shallow, only five-foot deep. At the bottom, it split into two passageways. The soldiers said one led to the house across the street and the other to an exit at the back of the house.

The Scout Rangers took me there. The entrance was big enough for me to squat. Eight feet in, the tunnel started to diverge into two passageways: one led to the entrance of the house and the other seemed to lead to a nearby street which had a relatively new sewage line.

I did not dare go farther. The tunnel has not been fully cleared. Imagining the last few moments before the house was taken over by the scout rangers, the sniper might have used the tunnel to escape either to the house across the street or to the sewage line.

The operation to take over the house took two days and a whole company of elite soldiers. Their enemy — not less than five but no more than 10 — all managed to escape.

As we made our way out of the compound, the soldiers led me to an adjoining house, which was completely burned to the ground, except for its concrete walls. They said that just before they overran the snipers house, a fire broke out spreading to nearby houses — a terrorist tactic, according to soldiers, to cover their escape and to deny government forces the use of the sniper’s house as a defensive position.

We finally exited onto the street where soldiers pointed to a blown up hole in the sewage line. They had to do it, they said, in an attempt to intercept the escaping terrorists. But the bad guys slipped away just the same.

The Scout Rangers pointed out that this was a classic example of how the terrorist group had managed to elude them and hold on to the city for more than four months.

Collapsed mosque

We then board a military truck and made our way to another part of Marawi. Snaking our way around collapsed buildings and burned down houses, it became increasingly clear how tough the battle to retake Marawi had been.

The truck stopped near the Marawi City Police Station. This was one of the first places attacked by the terrorist group at the start of the crisis in late May.

Beside it was a toppled minaret of what was once a mosque. The whole structure had collapsed and the buildings around it, all reduced to rubble.

The soldiers claimed the mosque collapsed because its walls had been weakened by repeated rocket propelled grenade strikes by the terrorists themselves from inside the structure. Wanting to hit the tanks positioned outside, the terrorists, the Scout Ranged told me, would apparently fire their RPG’s from inside the mosque through their sniper holes. Some went through but others exploded on the walls of the mosque itself.

But the soldiers admitted that a bomb from an FA-50 fighter jet that made a direct hit on the building next to it could have also contributed to the damage.

This was a scene from probably one of the most intense battles throughout the almost five-month long effort to retake the city.

Not included in their sector, the Third Scout Ranger Battalion was ordered to this mosque to help members of the 51st Infantry Battalion. The Army unit suffered heavy casualties while trying to clear the mosque, with more than 40 getting wounded in a single day.

When the Scout Rangers arrived, the wounded soldiers have been evacuated, save for one. The soldier lay motionless in the open, any attempt to rescue him thwarted by intense enemy fire from inside the mosque. Even after realizing the soldier was dead, the Scout Rangers refused to give up.

A plan was made. They will inch their way to the mosque by building a wall made up sandbags and oil drums packed with soil. Protected by cover fire from a tank and their sniper, the soldiers rolled the drums to the open field, stood it upright and stacked sandbags on top. Under constant sniper and automatic gunfire, they did this repeatedly until the wall got longer and higher.

After almost three days, they got close enough for the elite Scout Rangers to safely cross the open field and enter the mosque. Faced with an elite force they failed to stop, the terrorists withdrew to the basement.

As the Scout Rangers picked the body of their slain comrade, not a single shot was heard from the terrorists, as if a sign of respect for an enemies’ resolve to bring back their own. Indeed as soldiers, against all odds, nobody should be left behind.

But when the smoke cleared, the Scout Ranger sniper who provided cover fire for the rescuers lay dead. He was hit in the chest by an enemy sniper.

When I got to the mosque, the wall was gone. They had to position the tank near the mosque to complete the clearing operation.

We made our way near the top of the rubble and entered a small gap in the collapsed building; a decomposing corpse of a cat greeted us as we slid inside. The mosque may have been destroyed but the first floor was still intact.

The soldiers then led me to the basement. The place was pitch black with only our flashlights illuminating our way as we navigated around pieces of concrete, personal belongings and furniture strewn all over the place.

The company commander of the Scout Rangers I was with said this place was rigged with improvised explosive devices (IED) when they first entered it. But the terrorists never got to detonate the explosives as they fled.

Inside, the soldiers pointed to more tunnels, one of which still had a sleeping mat inside. The tunnel had been dug on the side of the wall connecting the adjoining buildings.

It took the Scout Rangers two more weeks to flush out the terrorists holed up in the entire block. Trained mainly in jungle warfare, the Scout Rangers learned to clear buildings as they went along.

We emerged on the other side of the block approximately 50 meters from where we entered. In front of us were the ruins of Padian, the sprawling old market of the city.

The soldiers said this was also one of the key reasons why the terrorists managed to survive in those five months. The market had hundreds of stalls selling everything from dry goods to grocery items and even medicine. And with Ramadan about to start when the crisis began, most food stores already had their month-long supply delivered. The terrorists had everything they needed inside the main battle area.

The soldiers said this was also one of the key reasons why the terrorists managed to survive in those five months. The market had hundreds of stalls selling everything from dry goods to grocery items and even medicine. And with Ramadan about to start when the crisis began, most food stores already had their month-long supply delivered. The terrorists had everything they needed inside the main battle area.

This indicates that the militants had an excellent planning level. They took into consideration almost all issues including long-term material security of their actions (comment – S.K.)

As we made our way to the exact spot where terrorist leaders Hapilon and Omar Maute were killed, I heard several explosions and a couple of gunfires.

Just part of the ongoing clearing operation, the soldiers said. At the outskirts of the city block where the terrorists made their last stand, we were stopped.

A radio communication came in telling everyone in the area to stay put. A huge detonation will be carried out.

In the building where we sheltered, two huge holes on the concrete floor indicated that the terrorists had tried to dig a tunnel, but they only got to about three feet. Up to the last minute, it seemed the terrorist group tried to employ their tunneling technique.

Concrete jungle

On one side of the room, three crates of Molotov bombs made from soft drink bottles lay unused. The scout rangers said these gasoline-filled bottles were extensively used by the terrorists in burning buildings and houses that they would abandon before escaping.

In several instances, the terrorists would use these Molotov bombs to torch houses with soldiers inside. The body of two government forces last to be recovered died this way, the soldiers told me.

Ten minutes later, I heard a muffled but thunderous explosion. Then we were finally given the «all clear» signal to proceed.

On the road where the two terrorist leaders had been gunned down, two tanks still stood guard. The area has not been fully cleared.

The two Scout Rangers who pulled the terrorist leaders from the street told me they had no idea that the two men sprawled face first on the dirt road were high-value targets. Only when they turned one over did they recognize Hapilon.

The two Scout Rangers who pulled the terrorist leaders from the street told me they had no idea that the two men sprawled face first on the dirt road were high-value targets. Only when they turned one over did they recognize Hapilon.

The Scout Rangers were very familiar with the man. After all, they had long been hunting down the Abu Sayyaf leader in the jungles of Sulu and Basilan for years. And outside the confines of Hapilon’s jungle territory, government troops finally got their target in the concrete jungles of Marawi.

Main battle area

As we left the area, one Scout Ranger commented how it was so easy for people to say that too many government forces got killed in the operation to retake Marawi, 165 to be exact. How people said the military seemed to have taken far too long and the destruction far too much.

“But they were not here”, the Scout Ranger said. “We were. And we won”.

I would later learn while I was in the area, at least one building still had five to eight terrorists holed up inside. Over a week after Hapilon and Omar Maute were killed and days after the military declared the combat operation was over, the fighting has not stopped.

The source said for four days, government troops tried to flush out terrorists hiding in a basement of one of the buildings in the area where I had been. First with tear gas, then with hand grenades and even IEDs, and later with burning tires. But the soldiers were still met with automatic gunfire when they tried to enter the building.

One solution was proposed. Collapse the whole building. The source said he didn’t know if this was done. The Philippine Army denied such a plan was carried out.

The explosions from inside the main battle area were controlled detonation of unexploded bombs and IEDs, the military said. That’s when I recalled the thunderous explosion I heard while inside the battle area.

The war may be over, but the mystery of the main battle area remains.

Conclusion

165 Philippine soldiers were killed and another 1,800 were injured during the country’s bloodiest battle since the World War II. 965 terrorists were eliminated and 3 were captured, but the total number of the militants was estimated to be around 1,000.

“Officials have identified the remains of about 40 foreign fighters from Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore. They are working to identify several, apparently Arab, bodies found on the battlefield”, — Colonel Brawer said.

“Philippine forces rescued 1,700 civilians from the battle zone, but the militants shot 47 in the early days of the crisis and forced others to fight on their side”, — he added.

Marawi’s obliterated urban development will take years to revive. However, some parts of the city are only lightly damaged and the residents of 9 neighborhoods have already returned back. It is expected that inhabitants of another two districts will also return over the next couple of weeks.

But those who lived inside the main battle area won’t see their homes any time soon.

Whose profit?

As seen in the article, the Americans have responded to Duterte’s plea rather operatively. And it is completely understandable considering strained relations between Rodrigo Duterte and former U.S. President Barack Obama. United States want to counteract the growing influence of China and Russia on the Philippines as well. So now they have considerably strengthened their positions in the country.

One can also assume that the previous Obama administration being dissatisfied with the rebellious behavior of the popular Philippine leader may have had a finger in the pie of this conflict. Some CIA structures were probably interested in financing the Mindanao unrest like they did in Syria earlier.

In theory this undercover politics should have been ceased after U.S. President Trump election who is sort of friend with Rodrigo Duterte. But you never know in advance. The seeds of conflict between Philippine Muslim minority and Christian majority can give a new crop of insurrection at any time.

Author: Sergey Kozlov

Translation: Dmitry Saloff

ANNA News

English

English Deutsch

Deutsch Italiano

Italiano Francais

Francais Espanol

Espanol

Для того чтобы оставить комментарий, регистрация не требуется